Today’s CSS is a far cry from that of its early days in the mid to late nineties. Like other web technologies, CSS’s capabilities are being stretched to its absolute limits by the public’s insatiable demand for slick and responsive web apps. In fact, much of the requirements of mobile apps have led web development into forays far from its original large screen target-base. In today’s article, we’ll examine some of the more mobile-oriented CSS techniques that have emerged amidst the modern mobile device landscape.

The Flexible Box Layout Module

Also known as the Flexbox, this W3C Candidate is a new layout mode in CSS3. It ensures the predictable behavior of elements when the page layout must accommodate different screen sizes and a variety of devices.

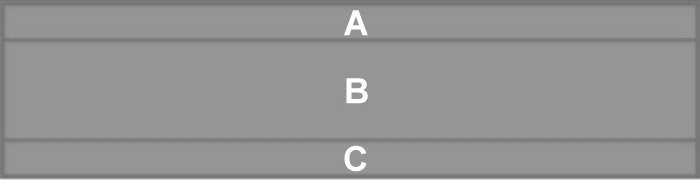

One of the best features of the Flexbox is that it’s possible to change the direction of the elements so that they are presented horizontally in wide screens and vertically in narrower ones, using the flex-direction property. To illustrate, here is some CSS defining three classes:

.a, .c {

flex: 1;

}

.b {

flex: 3;

}

.layout {

display: flex;

}

/* Narrow */

@media only screen and (max-width: 480px) {

.layout {

flex-direction: column;

}

}

/* Wide */

@media only screen and (min-width: 481px) {

.layout {

flex-direction: row;

}

}

The flex property specifies the length of the flex item, relative to the rest of the flex items inside the same container. Hence, the .b (center) element would take three times more space than the two outer ones (.a and .c).

The flex-flow property is a sub-property of the Flexible Box Layout module. It is a shorthand for flex-direction and flex-wrap.

.layout {

flex-flow: row wrap;

}

Hardware Acceleration using CSS Animation

Animations are a feature of rich applications that help distinguish them from static web pages. Especially when applied to GUI components, smooth animations provide the user with a native-like experience. Unfortunately, there are still developers who achieve their animations by manipulating the left/top/right/bottom CSS properties instead of using css-transform or animate. Using the later shifts reflows and repaints to the compositor thread, which is handled by the GPU (Graphics Processing Unit).

The following code slides an image into place from left-to-right after a 2 second delay:

<style>

.wrapper {

position: relative;

overflow: hidden;

width: 600px;

height: 370px;

border: 1px solid black;

}

#slide {

position: absolute;

left: -600px;

width: 600px;

height: 370px;

background: blue;

-webkit-animation: slide 0.5s forwards;

-webkit-animation-delay: 2s;

animation: slide 0.5s forwards;

animation-delay: 2s;

}

@-webkit-keyframes slide {

100% { left: 0; }

}

@keyframes slide {

100% { left: 0; }

}

</style>

<div class="wrapper">

<img id="slide" src="https://s3.amazonaws.com/content.sitezoogle.com/u/107988/124d7075bd224fceaecf8172ca200f088653378f/large/IKnew-nologo.jpg?1373829530" />

</div>

You can observe the code in action on Codepen.

Momentum-style Scrolling

By default, web pages on iOS implement “momentum” style scrolling where a flick of the finger sends the web page scrolling, going until eventually slowing down and stopping as if by friction. However, elements with scrolling do not inherit this same behavior, that is unless you add it back with a special webkit property called -webkit-overflow-scrolling. To activate “momentum” style scrolling, include the overflow-x or overflow-y property with a value of “scroll”, along with the -webkit-overflow-scrolling property set to “touch”:

.widget {

width: 300px;

height: 500px;

overflow-y: scroll; /* has to be scroll, not auto */

-webkit-overflow-scrolling: touch;

}

Here‘s a demo that compares element scrolling both with and without -webkit-overflow-scrolling: touch.

Sticky Positioning

Sticky positioning is a hybrid of relative and fixed positioning. The element is treated as relative positioned until it crosses a specified threshold, at which point it is treated as fixed positioned.

Until now, to achieve the sticky effect, sites designers had to setup scroll event listeners in JS. In general, scroll handlers are never a good idea because it places a heavy burden on the rendering engine and may result in choppy UI performance. Many modern browsers are implementing hardware accelerated scrolling to improve UI performance. Unfortunately, employing JS scroll handlers causes browsers to fall back into the slower CPU mode rather than using the GPU. Declaring sticky positioning in CSS is the defacto standard for letting the GPU manage scrolling.

By simply adding position: sticky (vendor prefixed), we can tell an element to be position: relative until the user scrolls the item (or its parent) to be 15px from the top. At top: 15px, the element becomes fixed:

.sticky {

position: -webkit-sticky;

position: -moz-sticky;

position: -ms-sticky;

position: -o-sticky;

top: 15px;

}

Here‘s a demo that sticks the header to the top of the screen once you scroll down to a certain point. Just keep in mind that position: sticky is only supported on some browsers.

Transition Effects

Like animations, transition effects are another feature of web apps that give the user a more native-like experience. Three of the most common UI transition effects on web apps that target mobile devices are slide, flip, and rotate. Some of these transitions can get a bit heavy on “code”, so we’ll leave that for a future article, but there are some excellent slide, flip, and rotation demos on Codepen that you can explore at your leisure.

Conclusion

Although browser-based web apps can only approximate the look and feel of native apps, modern CSS3 is helping to blur the lines between the two. In doing so, it is opening new avenues of development practices that are separate and distinct from those of traditional web pages.